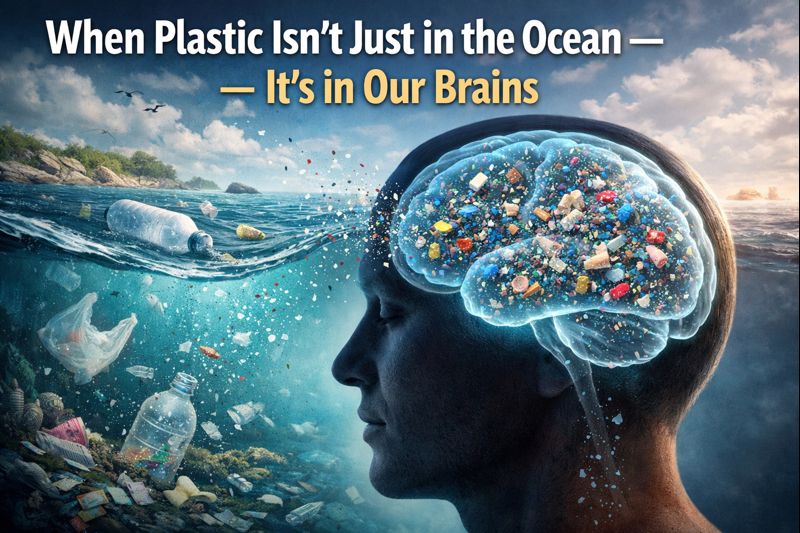

For years, plastic pollution has been described as an environmental issue — a problem harming oceans, marine life, soil, and the broader ecosystem. But new research reveals something far more unsettling: plastic is no longer just an ecological problem. It is a human health problem. And according to recent landmark studies, including research published in JAMA Network Open, microplastics are now being detected in some of the most protected organs in the body, including the human brain.

This discovery is reshaping the global conversation about plastic exposure. What was once considered an external environmental threat is now an internal biological one. And the implications for neurological health, longevity, and chronic disease risk are becoming impossible to ignore.

This article unpacks the latest research, why microplastics matter for human biology, and how you can reduce your exposure today.

Microplastics are fragments of plastic less than 5 millimeters in size. Many are much smaller — invisible to the human eye. They originate from a wide range of sources, including:

There are two general categories:

Even more concerning are nanoplastics, particles so small they behave more like chemicals than solids. These particles may penetrate tissues, cross biological barriers, and accumulate in organs in ways we are only beginning to understand.

Humans absorb microplastics through three main pathways:

Given that plastic production and waste continue to climb worldwide, exposure is increasing — and so are concerns about what these particles are doing once they enter the body.

One of the most significant scientific revelations came from a 2024 case series published in JAMA Network Open, which documented microplastics in the olfactory bulbs of human cadavers. This is the area of the brain connected to the sense of smell and one of the few pathways where external particles can bypass the blood–brain barrier.

Researchers analyzed brain tissue from 15 human donors and found:

This study demonstrated that inhaled microplastics can travel through the nasal cavity and enter the brain directly via olfactory nerves. Until recently, many scientists believed the blood–brain barrier was sufficient to prevent plastic infiltration into brain tissue. These findings overturn that assumption.

A second, larger study published in early 2025 expanded the concern dramatically. Researchers examined brain tissue, liver, kidneys, and lungs from human cadavers and found:

This does not prove that microplastics cause dementia. However, the correlation suggests a potential link between chronic exposure, neuroinflammation, and cognitive decline. It also indicates that microplastics accumulate in the brain over time and may not be effectively cleared by the body.

One researcher described the accumulated quantity of nanoplastic particles found in some brains as comparable to a spoonful of plastic fragments — an amount that builds up quietly over a lifetime.

Research on microplastics in humans is still young, but early findings reveal several concerning biological effects.

Microplastics appear to activate inflammatory pathways in tissues. Chronic inflammation is a well-documented driver of:

Even low-level chronic exposure may have cumulative effects over time.

Plastics are known carriers of chemicals such as:

These chemicals can interfere with hormone signaling, affecting thyroid function, estrogen balance, fertility, metabolism, and immune resilience.

Microplastics are not inert. They can cause physical stress inside tissues, especially when sharp or irregularly shaped.

Nanoplastics may cross:

This could explain why microplastics are now found in organs once thought to be protected, including fetal tissues and the central nervous system.

One of the most troubling findings from recent research is that the concentration of microplastics in human brain tissue appears to be rising over time. Because humans didn’t evolve with synthetic plastics, the body has no efficient mechanism to eliminate them. This suggests accumulation may be lifelong.

Beyond the brain, studies have detected microplastics in:

This indicates that microplastics are not localized contaminants — they are systemic. Once inside the body, they circulate, deposit, and interact with biological systems in ways still being studied.

The brain is uniquely sensitive to inflammation, toxins, and oxidative damage. When microplastics or nanoplastics enter brain tissue, they may disrupt neural function in several ways:

While definitive human outcomes are still unknown, these mechanisms highlight why the discovery of microplastics in the human brain is so concerning.

Although microplastics affect all humans, there are specific considerations for women:

More research is needed, but the intersection of microplastics, hormones, and neurological health is an emerging area of concern.

We cannot completely eliminate exposure — but we can meaningfully reduce it. These strategies are backed by environmental health research and practical for everyday life.

Use these for water bottles, food storage, and reheating food. Plastics shed microplastics more readily when stressed by heat, scratches, or prolonged use.

Heat accelerates plastic degradation and chemical leaching.

Studies show processed foods contain more microplastics than whole foods, likely due to both processing and packaging.

Tap water filtered through activated carbon or reverse osmosis contains fewer microplastics than bottled water.

Indoor air often contains more microplastics than outdoor air. Strategies include:

Polyester, nylon, and spandex release microfibers with every wash. Using guppyfriend bags or microfiber filters can significantly reduce shedding.

Plastic bags, straws, utensils, and takeout containers all shed microplastics as they degrade.

Personal choices matter — but systemic changes scale far faster. Support policies that reduce plastic production, improve recycling technology, and regulate harmful additives.

The discovery of microplastics in human brain tissue is a turning point. We have crossed a threshold where the plastic crisis is no longer external. It is internal. It is biological. And it raises important questions for public health, environmental policy, and long-term neurological wellness.

We do not yet know exactly how microplastics impact health over decades. But we do know:

In other words, the concern is justified — and the time to act is now.

Reducing your personal exposure is a powerful start. But addressing the deeper issue requires collective awareness, scientific urgency, and a commitment to reducing our reliance on single-use plastics.

Plastic pollution is no longer just about oceans and rivers. It is about our cells, our tissues, and our brains. The more we learn, the clearer it becomes: protecting our health means rethinking our relationship with plastic.