Fasting has become one of the most discussed topics in modern health, often framed as a diet trend or a metabolic hack. But fasting is neither new nor artificial. It is one of the oldest biological rhythms humans have ever experienced. Long before calories were counted or meals were scheduled, periods of eating were naturally followed by periods of not eating. The human body did not merely tolerate this pattern — it evolved because of it.

Understanding fasting requires stepping away from diet culture and into physiology, history, and evolutionary biology. When we do that, fasting becomes less about restriction and more about metabolic flexibility, the body’s ability to shift fuel sources, conserve energy, and activate repair mechanisms when food is temporarily unavailable.

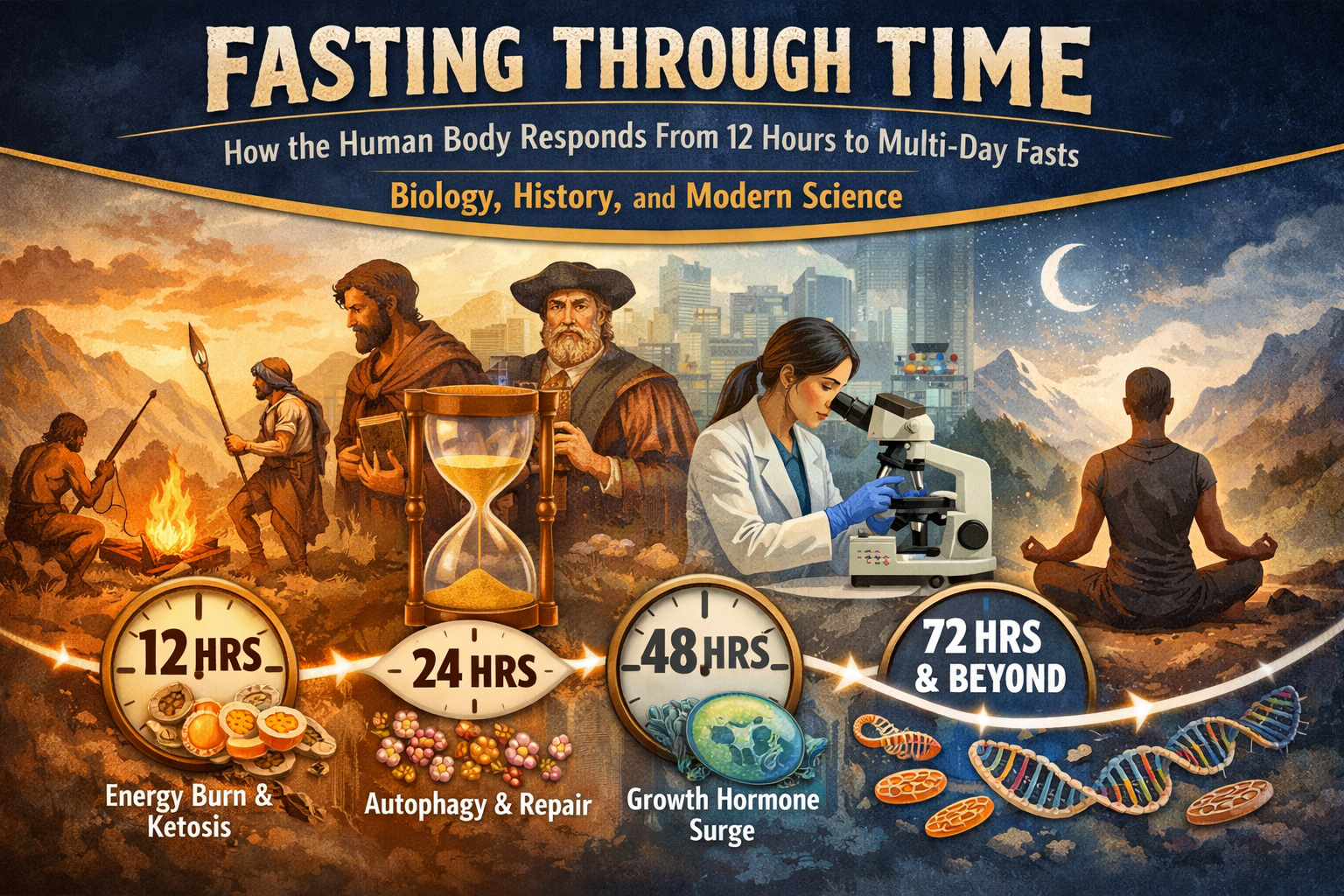

Modern research now allows us to see what ancient humans could only experience. We can measure insulin, ketones, hormones, inflammatory markers, and cellular signaling pathways. And what that research shows is that different fasting lengths produce distinct biological effects, each with its own purpose and limitations.

For most of human history, food availability was unpredictable. Hunter-gatherer societies did not eat three meals a day with snacks in between. Meals depended on successful hunts, seasonal plant availability, and environmental conditions. Anthropological evidence suggests that early humans frequently experienced periods of fasting ranging from overnight to several days, particularly during migration, drought, or failed hunts.

This reality shaped human metabolism. The ability to store energy efficiently during times of abundance and mobilize that energy during scarcity was essential for survival. The modern human body still carries these adaptations, even though our environment has changed dramatically.

Today, constant food availability keeps insulin elevated, suppresses fat mobilization, and limits entry into metabolic states that were once routine. Fasting reintroduces a rhythm the body recognizes, even if the modern mind resists it.

A twelve-hour fast is often dismissed as insignificant, but metabolically it represents the first meaningful shift away from continuous feeding. After the final meal is digested, circulating glucose begins to fall and insulin levels decline. The liver takes on the role of maintaining blood glucose by breaking down stored glycogen.

Human studies show that liver glycogen stores can be substantially reduced within 12–24 hours, depending on activity level and prior carbohydrate intake. This process marks the beginning of what researchers call the “post-absorptive state,” where energy comes increasingly from internal reserves rather than recent meals.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3946160/

Even at this early stage, fat oxidation begins to increase. Small amounts of ketone bodies appear in circulation, signaling the body’s gradual transition toward fat-based fuel use.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19570763/

Historically, this overnight fast was the default human condition. Without artificial lighting and late-night eating, fasting aligned naturally with circadian rhythms. Modern research supports this alignment, showing that eating earlier in the day and allowing a prolonged overnight fast improves glucose regulation and insulin sensitivity.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31849586/

When fasting extends into the sixteen- to seventeen-hour range, the body’s reliance on stored glycogen diminishes further, and fat becomes a more prominent fuel source. Insulin levels fall low enough to allow efficient mobilization of fatty acids from adipose tissue, while glucagon and catecholamines rise to support energy availability.

This stage is central to the concept of metabolic flexibility — the ability to switch between glucose and fat without energy crashes or intense hunger. Research on time-restricted eating demonstrates that this fasting window improves insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, and mitochondrial efficiency in many individuals.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7809455/

Ketone production increases during this window, providing an alternative fuel for the brain. Ketones are not merely energy substrates; they act as signaling molecules that influence oxidative stress, inflammation, and gene expression.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5452224/

From an evolutionary perspective, this fasting length reflects the natural spacing between meals in hunter-gatherer societies. Food acquisition required time and effort, and the body adapted by becoming highly efficient at running on stored fat during these intervals.

At approximately twenty-four hours without food, most liver glycogen is depleted. This forces a more pronounced metabolic transition. Fatty acids become the dominant energy source, and ketone levels rise substantially. Insulin remains suppressed, allowing fat oxidation to proceed unimpeded.

This is the fasting duration where researchers observe significant changes in cellular signaling. Pathways associated with growth and nutrient abundance, such as mTOR, are downregulated. In contrast, pathways associated with stress resistance and cellular maintenance become more active.

One of the most discussed processes activated during prolonged fasting is autophagy, the body’s system for degrading and recycling damaged cellular components. Autophagy is active at baseline, but nutrient deprivation amplifies these signals. While direct measurement in humans is challenging, mechanistic studies and biomarker data strongly support increased autophagic activity during extended fasting.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10509423/

This shift toward cellular maintenance helps explain why fasting has been associated with improvements in metabolic health, inflammation markers, and cellular efficiency in certain populations.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28202779/

By thirty-six hours, ketone production is well established, and the body is fully operating in a fat-dominant metabolic state. Studies examining lipidomics during prolonged fasting show widespread changes in lipid species, reflecting a systemic shift toward fat utilization and metabolic remodeling.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10513913/

Hormonal signaling continues to evolve. Growth-promoting pathways remain suppressed, while stress-response systems that enhance cellular resilience are activated. This includes reductions in insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), a hormone involved in growth and proliferation.

Research in animal models and limited human data suggest that reductions in IGF-1 during fasting may support tissue maintenance and immune system regeneration. A widely cited study published in Cell Stem Cell demonstrated that prolonged fasting reduced IGF-1 signaling and promoted stress resistance and regenerative capacity in hematopoietic stem cells.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24905167/

While these findings are compelling, it’s important to emphasize that fasting does not guarantee regeneration. It creates a biological environment where repair processes are favored, but outcomes vary based on age, baseline health, and refeeding practices.

Beyond forty-eight hours, fasting enters a different physiological category. The body is deeply ketotic, insulin is extremely low, and fat is the primary fuel source. Clinical reviews of prolonged water-only fasting show that humans can tolerate this state under supervised conditions, with careful attention to hydration and electrolytes.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11494232/

At this stage, fasting exerts systemic stress. Cortisol and other stress hormones may rise to support energy mobilization and blood glucose stability.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5851137/

This stress is not inherently harmful — in fact, it is part of the adaptive response — but it underscores why longer fasts should be approached intentionally and not treated as lifestyle habits.

Historically, this level of fasting occurred during prolonged scarcity or environmental hardship. Survival depended on metabolic efficiency, not comfort. Modern fasting at this length is best viewed as a therapeutic intervention, not a routine practice.

Fasting is not only a biological phenomenon; it is deeply woven into human culture. Many religious traditions incorporate fasting as a practice of reflection, discipline, and renewal. These practices developed independently across civilizations, long before the mechanisms of insulin, ketones, or autophagy were understood.

What modern science now reveals is that these traditions often aligned with human physiology in profound ways. Periods of fasting altered awareness, energy use, and physical sensation, reinforcing the connection between body, mind, and environment.

A three-day water fast sits at a unique intersection of physiology. It is long enough to engage ketosis, suppress insulin and IGF-1, and activate cellular maintenance pathways, yet short enough that, in generally healthy adults, the risks remain manageable with proper electrolyte support and refeeding.

This balance is why three-day fasts are often used as metabolic resets rather than endurance challenges. The goal is not deprivation, but adaptation — allowing the body to temporarily step out of constant nutrient processing and into a state of metabolic efficiency.

This January, I’ll be guiding a three-day water fast with electrolytes, grounded in this science and supported with education throughout the process. This is not about extremes or willpower. It is about understanding the biology your body has carried for thousands of years and using it with respect and intention.

Fasting is not something humans invented. It is something we evolved with — and something we can relearn how to use wisely.